|

Walter Ralegh (his preferred spelling, and pronounced “Raw-lee”) met his grisly end on the scaffold four hundred years ago today. Condemned to a traitor’s death in 1603, having plotted against King James I, he lived on a kind of death row in the Tower of London for the next 14 years. Briefly freed to follow his dream of finding El Dorado in the South American jungle, he was, as his latest biographer Anna Beer notes, little more than a “dead man walking”, and when he returned to England having failed to find the fabled golden city, King James lost patience, and had him executed. By then, however, Ralegh had secured his place in history. Poet, soldier, politician and adventurer (listen to Professor Jerry Brotton’s documentary on Ralegh’s search for El Dorado), he is erroneously credited with introducing the potato to England and he is perhaps best remembered in school textbooks as the gallant courtier who spread his cloak over a puddle so that Queen Elizabeth I wouldn’t get her feet wet. But Ralegh’s greatest legacy was America. As I and my co-author John Butman show in our book, New World, Inc: How England’s Merchants Founded America And Launched The British Empire (Little, Brown and Atlantic Books, 2018), he was the first successful colonial entrepreneur, catalysing the quest for America and influencing the first generation of pioneer-settlers. Sir Walter Ralegh—who died on 29 October 1618 Ralegh’s older half-brother, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, was the true visionary of the New World. Sir Winston Churchill called him “the first English pioneer of the West”. From the 1560s, Gilbert prepared detailed dossiers on settlement, and in 1578, Queen Elizabeth granted him rights to settle people in Newfoundland and elsewhere. Five years later, he claimed Newfoundland for England, but died on his return home, and it was left to Ralegh to carry on where he had left off.

Practical in a way that Gilbert never was, Ralegh put together a dream team of experts who managed a well-organised mission to the New World. Richard Hakluyt, the first great champion of English prose, was Ralegh’s marketer-in-chief; Thomas Harriot, sometimes regarded as England’s answer to Galileo, was Ralegh’s day-to-day fixer, and arguably the first European to learn Algonquin; and John White, a watercolorist of genius, presented English people with their first glimpse of the New World. Ralegh, himself, took charge of the fundraising, securing lucrative perquisites from Elizabeth, who diverted state resources towards Ralegh’s imperial endeavour in an early instance of what diplomatists call “plausible deniability”: if Ralegh ever got caught by Spain, England’s great rivals and the superpower of the day, Elizabeth could claim her errant courtier was acting on his own. Ralegh had planned to lead the voyage to America. He, after all, had been given the right to call himself Lord of Virginia, with a special coat of arms. But as the day of departure neared, Elizabeth refused him permission to travel: she wanted him by her side. Changing plans, Ralegh gave the command to his kinsman, Sir Richard Grenville, who served as admiral of the fleet. In 1585, the ships reached modern-day North Carolina, establishing a colony on Roanoke Island in a land Ralegh called Virginia, in honour of Elizabeth, the “Virgin” Queen. The colony might have survived, but for a chapter of accidents and the onset of the hurricane season. The colonists returned home in 1586, after more than a year in the New World. When a second colony was sent out in 1587, there was great hope that the settlers would remain in America for good. As it turned out, they did stay in America—although not necessarily because they wanted to. In 1588, England was engulfed by crisis—the Spanish sent an Armada with the express intention of escorting an invading army to London—and Ralegh was unable to send a resupply vessel to Roanoke. By the time a supply vessel did reach Roaonoke—in 1590—the settlers were nowhere to be seen. In time, these settlers would enter American legend as “the lost colonists”. But for years, Ralegh continued to believe that they were still alive, sponsoring a series of searches in 1598, 1599 and 1600. He had an ulterior motive for doing so: while they were alive, he could continue to claim his title to the lordship of Virginia. In the end, his imprisonment robbed him of any rights in the New World. The baton passed to a new generation of entrepreneurs and adventurers. But some of the new leaders drew their inspiration from Ralegh. As a young man, Sir Thomas Smythe, the head of the Virginia Company (which founded Jamestown, the first permanent English colony), had led the syndicate of investors who assumed control of Ralegh’s Roanoke colony in the late 1580s. From bitter experience, he learned the paramount importance of resupplying English settlements on the other side of the Atlantic. Also, Bartholomew Gosnold, one of the leaders of Jamestown before his tragic death a few months after the founding of the settlement, ensured that the account of his first voyage to America (when he gave Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard their names) was dedicated to Ralegh. Throughout Ralegh’s incarceration in the Tower of London, the very survival of Jamestown—the successor to Roanoke—looked to be in doubt. Would it go the same way as Roanoke? This question may have crossed his mind as he prepared to meet his maker on 29 October 1618. As we know, Jamestown did survive, and its prospects were greatly increased just a few weeks after Ralegh’s death. In November, Sir Thomas Smythe and his fellow Virginia Company leaders, issued a “Great Charter”—a very deliberate reference to the medieval Magna Carta, the four-hundred-year-old document that provided the foundation for English individual rights. As part of the charter reforms, the settlers were authorised to establish the House of Burgesses, which one historian has called “the first freely elected parliament of a self-governing people in the Western World”. Set free to run their own affairs and keep most of the proceeds of their own labour, the settlers managed an economy that was buoyed by the successful farming of tobacco—the plant that Ralegh had made fashionable in the Elizabethan court. In a few weeks’ time, the Pilgrims will once again be honoured as the true founders of America—as they are every Thanksgiving. But it was Sir Walter Ralegh, dead before they even set foot on Plymouth Rock, that made their story, and America's, possible.

0 Comments

Prince Henry Charles Albert David Wales—better known as Prince Harry—is doing a sterling (or, rather, top dollar) job to enhance Britain’s special relationship with America. Throughout his spectacular wedding ceremony, when he married Meghan Markle, his Los Angeles-born wife, with all the majesty that Britain can bring to such occasions, America was given a starring role: Bishop Michael Curry, head of the Episcopal Church in the US, gave a bravura performance, as he delivered a rousing address on the redemptive power of love; the gospel Kingdom Choir swayed from side to side as they sang Ben E. King’s Stand By Me; and, for the carriage procession, which took place in the shadow of the world’s oldest inhabited castle, the people of Windsor waved the Stars and Stripes alongside the Union “Jack”. Prince Harry and Meghan Markle walk down the steps of St. George's Chapel in Windsor as a newly-married couple But when he walked down the aisle of Windsor Castle’s St. George’s Chapel with his bride, Prince Harry was walking, metaphorically speaking, in the footsteps of another ginger-haired royal called Prince Henry—who was born more than four centuries ago. The earlier Prince Henry was destined to become King Henry IX. The great-great-great nephew of Henry VIII—the tyrant-king who had six wives—Henry Frederick Stuart was born to the future King James I in 1594. Heir to the throne (unlike Prince Harry, who’s now sixth in line), Henry was a renaissance prince, tutored in the arts and sciences, and schooled to be a king. Prince Henry in a painting which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. It was produced around the time that Henrico was founded in Virginia A serious boy, he was barely a teenager when he started to take great interest in the efforts of English merchants to expand the country’s territory in the New World. Among other things, he championed the cause of the first great colonial adventurer, Sir Walter Ralegh, who was then imprisoned in the Tower of London on trumped up charges of treason. “No King but [my] father would keep such a bird in a cage,” he was heard to say. James was really only interested in the New World as a source of wonders for his exotic menagerie. As Shakespeare’s patron, the earl of Southampton, once noted: “The King is eager to have one of the Virginia Squirrels that are said to fly.” But young Prince Henry, with perhaps half an eye on the day when he would succeed his father and inherit an expanding empire, was altogether more engaged in the commercial ventures to America. And the English merchants who ran the Virginia Company—founded to finance new trading settlements across the Atlantic—capitalised on his enthusiasm. In 1607, when the first colonists reached the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on the east coast of America, they named their landing spot Cape Henry, in honour of the future king. It was the first American territory to be named after a male English royal—Virginia having been named after Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen”. They didn’t settle on this windy headland, however. Sailing on, they travelled up what became known as the James River, and named their colony Jamestown—both river and settlement honoring King James I. But they eventually tired of this marshy, malarial place, regarding is as “unwholesome” and only good as a port. So they went in search of another place to establish a new “principal residence and seat” for the settlement. They found it further up the James River, not far from where Richmond, the capital of Virginia, stands today. The colonists’ leader, Sir Thomas Dale, a grit-hard soldier, set his men to work on building a new town. According to one of the settlers, it eventually featured “three streets of well framed houses, a handsome church and…store houses, watch houses, and such like.” Proud of the new settlement, Dale christened it Henrico (also known as Henricus)—in honor of Prince Henry. From this point onwards, Henry was recognized for his efforts to forge links between England and America. Even the Spanish ambassador, representing a country that was the superpower of that time, noted that the young prince was starting to be regarded as “the Protector of Virginia.” But then, tragedy struck. In 1612, the year after Henrico’s founding, Prince Henry suffered a terrible typhoid fever. He never recovered, dying on the 6th November, aged just 18 years. He was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. Dale mourned the passing of the great hope of Virginia—and he feared for the future of the fledgling settlement. Prince Henry, he wrote, was “the Great Captain of our Israel, the hope to have built up this heavenly new Jerusalem”. With his passing, “the whole frame of this business fell into his grave.” Happily, Dale’s gloomy prediction did not come to pass. The following year, one of the farmer-colonists, John Rolfe, produced his first crop of Nicotiana tabacum. The sweet tobacco leaf proved a great commercial success. And then, the year after that, Rolfe came to the rescue again, when he met a Powhatan princess in Henrico: Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas. When they married, their union marked the end of the brutal five-year Anglo-Powhatan war. In its way, it was a testament to the redemptive power of love. Economically self-sufficient, and finally enjoying peaceful relations with their neighbours, the English settlers could look forward to a hopeful future, as I explain in my new book, co-authored with John Butman: New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (Little, Brown). Perhaps Prince Harry’s union with his American princess has the potential to spark similar feelings of hope. The world is entering a troubled and uncertain time. But as Bishop Curry put it in his peroration, when we discover the redemptive power of love, “we will make of this old world—a new world”. To purchase New World, Inc: The Making of America by England's Merchant Adventurers (Little, Brown, 2018)

Amazon: www.amazon.com/New-World-Inc-Englands-Adventurers/dp/0316307882/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1526753780&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc Barnes & Noble: www.barnesandnoble.com/w/new-world-inc-john-butman/1126682733?ean=9780316307888#/ To pre-order (in the UK) New World, Inc: How England's Merchant Adventurers Founded America and Launched the British Empire (Atlantic Books, 5 July 2018) Amazon: www.amazon.co.uk/New-World-Inc-Englands-Merchants/dp/1786495473/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1526753851&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc Waterstones: www.waterstones.com/book/new-world-inc/john-butman/simon-targett/9781786495471 WH Smith: www.whsmith.co.uk/products/new-world-inc-how-englands-merchants-founded-america-and-launched-the-british-empire-main/9781786495471 For more on Henrico, go to Henries Historical Park henricus.org For more on Cape Henry www.nps.gov/came/index.htm

organised these voyages. A serial entrepreneur, the driving impulse for his space activity is a looming apocalypse. In his public pronouncements on his project to send a manned mission to Mars, Musk points to the likelihood of a “doomsday event”. He doesn’t know when it will happen, but he is certain that it will happen, and human beings need to be ready to evacuate the world. Likewise, Musk’s predecessors took action when England experienced its own existential crisis in the 1550s, after a cataclysmic economic collapse threatened to weaken the country and leave it at the mercy of larger, richer neighbours such as Spain and France. Staring national oblivion in the face, they put their petty rivalries aside and put their capital to work in the first of an unbroken chain of voyages in search of new markets that led, ultimately, to the settling of America in the early 1600s. Musk’s answer to the apocalyptic challenge has been to create a company, SpaceX. Its corporate motto is “Making Life Multiplanetary”. Similarly, the English merchants answer was to create a private company—the wonderfully named “Mysterie, Company, and Fellowship of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions, Islands, and Places Unknown.” But, in setting up a company, they were doing something truly innovative. The “Mysterie” was arguably the world’s first joint-stock company and, as such, the forerunner of all modern corporations, including SpaceX. For the next 50 years, these merchants and their successors inched their way towards America. Often, progress was slow: one step forwards, two steps back. But in the early 1600s, a more advanced version of the “Mysterie” emerged in the shape of the Virginia Company. Tasked with establishing a colony in what was then called Virginia, it was led by a man named Sir Thomas Smythe, who faced many of the same challenges as Musk today. The first was—and is—to “get there”. This wasn’t, and isn’t, easy. Although Smythe no doubt benefited from the fact that Europeans had crisscrossed the Atlantic for more than a century, the journey across the north Atlantic remained perilously unpredictable and there was still no English colony in North America. Similarly, although Musk is building on a long history of aeronautical endeavour—rockets have reached the Moon and robots have been sent to Mars—there has never been a manned mission to the Red Planet. Musk has designed the Falcon Heavy rocket, which underwent a recent successful blast-off, and caused CNN to talk of “a new space age”. At the same time, he is developing the so-called BFR transport system featuring a spaceship for astronauts. Smythe’s equivalent was the Sea Venture—a 250-ton ship purpose-built to carry colonists, not just cargo, to Jamestown. But unforeseen accidents can happen. Although the Falcon Heavy was launched without a hitch, a previous rocket blew up in a pre-launch test, forcing Musk to modify the likely time of a mission launch. Likewise, the Sea Venture was hit by a hurricane and broke up on the rocky reefs of the Bermuda Islands—or the Devil’s Islands, as they were known then. The sense of loss was deeply felt across England—to the extent that William Shakespeare drew on the dark episode for his final play, The Tempest. As it happened, everyone on the Sea Venture survived the shipwreck. But there was no satellite tracking system in those days, and the news took more than a year to filter back to England. By then, Smythe and his associates had solved the problem of “getting there”—time and time again. But getting there is one thing, “staying there” quite another. Smythe was haunted by the memory of Roanoke, the first English colony, which had been established by Sir Walter Ralegh in what is now North Carolina. The first settlers abandoned the place. A second group were left behind to fend for themselves—and they were never seen again. Unlike Matt Damon, in the movie The Martians, there was to be no happy ending for these pioneers. They entered American legend as “the lost colonists”. Smythe resolved to send regular supplies of food, clothing and other necessities. But it did not become self-sustaining until some settlers found new ways to make money—notably, by farming tobacco and leasing land. Eventually, the call went out for skilled artisans to help build the colony—and there were plenty of people willing to sign up. Musk’s Mars colony may follow a similar trajectory. There is already speculation that settlers could fund a colony by mining minerals from the nearby asteroid belt or by producing a pipeline of scientific innovations that could be patented. And Musk has said that, eventually, a Martian settlement will see “an explosion of entrepreneurial activity because Mars will need everything from iron foundries to pizza joints and night clubs”. But it will take years and years to make Mars sustainable—as it did with America. It was competition that ultimately spurred Smythe and his fellow London merchants to success: they rushed to beat rival Plymouth merchants to America and, under the terms of a royal charter, have the pick of the places to settle in Virginia. And it will be competition that spurs Musk. He is in a race to be the first to Mars—and he is currently targeting 2024 for the first manned mission to Mars. That’s a decade ahead of NASA. But Musk is not just in a race against rivals. He is in a race against time. In fact, we all are. And it is here that the two projects—the mission to Mars and the voyage to America—start to diverge. If English merchants had not triggered their search for new markets that led, after half a century of endeavour, to the settling of America, then England may not have survived as an independent nation, America may not have become the country it is today, and English may not have become the world’s lingua franca. Such are the “ifs” of history. But if Musk and other likeminded entrepreneurs fail to find a way to colonise Mars, and ultimately other planets, then the future of the human race is at stake. As Stephen Hawking, the English astrophysicist who died last month, once said, we face annihilation from several possible calamities: “It could be an asteroid hitting the Earth. It could be a new virus, climate change, nuclear war, artificial intelligence gone rogue.” For this reason, he said, he was “convinced” that “humans need to leave Earth and make a new home on another planet.” And we need to do so quickly. “For humans to survive,” he warned, “I believe we must have the preparations in place within 100 years.” It is a mighty task that has befallen our generation. Musk is leading the way, along with a few other entrepreneurs. Others are sure to follow. Perhaps the real story of who made America—England’s merchants, not her Pilgrims—can provide all of us with the inspiration to succeed. For England, read the human race. For America, read Mars—and survival in a new world. To purchase New World, Inc: The Making of America by England's Merchant Adventurers (Little, Brown, 2018): www.amazon.com/New-World-Inc-Englands-Adventurers/dp/0316307882/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1525107581&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc

To pre-order (in the UK) New World, Inc: How England's Merchant Adventurers Founded America and Launched the British Empire (Atlantic Books, 5 July 2018): www.amazon.co.uk/New-World-Inc-Englands-Merchants/dp/1786495473/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1525107760&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc For more on Elon Musk's Mars plans: www.spacex.com/mars Elon Musk photo: By Steve Jurvetson -https://www.flickr.com/photos/jurvetson/18659265152/CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40974345 Sir Thomas Smythe portrait: By Simon Van De Passe. National Portrait Gallery

exclude his own pupils from his remarks) displayed “an underlying sense of entitlement”. He didn’t use the word “snowflake”—a word that, among other things, has come to describe a generation of people with an inflated sense of their own uniqueness. But he might as well have done. What particularly irked him was an interview he conducted with a trainee teacher who, at the end of the conversation, asked him: “Why should I come to work for you?” For Mr. Robb, it was a deflating response. As he reflected in his blog: “There used to be a real sense of pride associated with doing ‘an honest day’s work’, whatever the role might have been. There was also a real sense of achievement among individuals who, having started on the bottom rung of a company’s ladder and having been recognised for sheer effort levels, or stand-out skill, were fortunate enough to work their way up the ladder.” Now, he believed, some youngsters approach job interviews “in the same way as they might approach buying a luxury holiday”. They “expect to be given a ‘one-in-a-million’ job, despite being one of millions of applicants”. In his blog, Mr. Robb praised James Dyson, a former pupil who embodied the kind of grit he wanted to see. The inventor spent 15 years developing his acclaimed vacuum cleaner, preparing more than 5,000 prototypes before finding success. Another suggestion for a role model with a Gresham connection is Sir Thomas Gresham, nephew of the school’s founder, whom I researched for my new book New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (co-written with John Butman and published by Little, Brown on 20 March 2018). A brilliant financier, who gave his name to Gresham’s Law (the fundamental economic principle that bad money drives out good money) and founded the Royal Exchange (London’s first bourse), he was one of the main investors in a series of pioneering voyages to China (the adventurers never got there): first via the supposed Northeast Passage (following the coast of the Eurasian landmass), and then via the fabled Northwest Passage through the icy waters of the Canadian Arctic. Born in 1518, Sir Thomas was, like many of the pupils at Gresham’s School today, raised in a privileged household. His father, a rich London merchant, was a renowned financier who rose to become Lord Mayor of London. Nowadays, that’s a ceremonial role. Back then, however, it carried real power. As a contemporary noted, there was “no public officer of any city in Europe that may compare in port and countenance” with the Lord Mayor of London. Young Thomas was given the very finest education money could buy: he was schooled at St. Paul’s, then and still among the top academies in the country (Gresham’s wasn’t founded until 1555). From there, he advanced to Gonville Hall (now Gonville & Caius College) in Cambridge, before acquiring a smattering of law at Gray’s Inn, the grandest of London’s famed inns of court and then the classic finishing school for the country’s aristocrats. After that, he might have expected to walk straight into the family business. But he didn’t do this—at least, his father wouldn’t let him. Under the old rules of patrimony, he was perfectly entitled to become a member of one of the most exclusive and powerful institutions in the country: the Worshipful Company of Mercers. In those days, membership of this august organisation conferred citizenship in London, and this was a requirement for anyone wishing to do business in England’s capital. But his father did not think it was a good idea simply to buy access. Yes, he wanted his son to follow in his footsteps and become a member, but not before working his passage and doing like everyone else who aspired to be a Mercer: complete a seven-year apprenticeship. As a teenager, Gresham was apprenticed to John Gresham, the school’s founder. We do not know what he thought about this idea at the time. But afterwards, he praised his “wise” father for giving him the opportunity to get “experience and knowledge” of different kinds of business, even though he “need not have been an apprentice”. Sir Thomas was driven to put his thoughts down on paper after seeing too many people enter the cloth trade without first having completed adequate training. In his opinion, they were producing shoddy work, and this was having a detrimental impact on England’s reputation as a cloth manufacturer. There might have been something of the protectionist in Gresham's stance. On the other hand, his thinking prefigured the modern view that to become a master of anything requires dedication, discipline and determination—or “grit”, as Mr. Robb puts it—and lots of time. As Malcolm Gladwell, the business writer, noted in his book Outliers, the magic number of hours needed to reach a world-class standard is 10,000. And years later, Sir Thomas gave generously to help those who were ready to help themselves and work their socks off. In his will, he set aside his palatial London mansion for use as a new college. Accordingly, in 1597, Gresham College, sited where the iconic Tower 42 (formerly known as the NatWest Tower) stands today, threw open its doors, offering free lectures to anyone who cared to attend them. The lecturers, paid more handsomely than the greatest professors at Oxford and Cambridge, were some of the most celebrated intellectuals of their day. For those willing to better themselves, Gresham College offered a priceless opportunity. They could turn up and hear Sir Christopher Wren, the architect, or Robert Hooke, the scientist, or John Bull, the composer. Even now, the college still offers free lectures, although it is no longer housed in Gresham’s mansion, which was demolished in the eighteenth century. Only the other week, my daughter and a friend, totally unbeknownst to me, took themselves off to hear the Oxford professor, Sir Jonathan Bate, give a lecture on Shakespeare. “Thrilling,” was her one-word precis. Five hundred years after his birth, Sir Thomas Gresham is a powerful role model. He was privileged—exceptionally so. He had every reason to feel a sense of entitlement. And yet he set all of his inherited advantages to one side, and worked hard, and deserved everything he got. His is an example well worth following—for the snowflake generation, or any other generation, for that matter. To Pre-order New World, Inc:

www.amazon.com/New-World-Inc-Englands-Adventurers/dp/0316307882/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1519928043&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc For Douglas Robb’s blog: www.greshams.com/senior/senior-overview/headmasters-blog/ For more on Gresham College: www.gresham.ac.uk

But, whatever its etymology, there is no doubt about the identity of the person who introduced the word “China” into the English language. His name was Richard Eden, a 35-year-old Cambridge scholar, who was working for a group of London merchants more than 450 years ago.

Born around 1520, when the tyrant Tudor monarch Henry VIII was on the throne (and still on his first marriage), Eden showed early promise as a student, advancing to Christ’s College, Cambridge when he was about 14 years old. He later moved to Queens’ College where, unusually for that time, he completed his bachelor’s degree. By the early 1550s, he was one of several brilliant young Cambridge men who occupied prominent positions at the court of the boy-king Edward VI, Henry’s son who had come to the throne at the tender age of nine—notably William Cecil, the administrator (whose descendants include the earls of Salisbury), Thomas Gresham, the merchant and financier (who gave his name to Gresham’s Law), and John Dee, the mathematician and cosmographer. This was a bleak time in England. Woollen cloth had long been the country’s principal source of income. As one contemporary noted: if one were to “divide our native commodities into ten parts…nine arise from the sheep’s back.” Yet, in the space of a couple of years, the market for English cloth in mainland Europe completely collapsed. Facing ruin, several of the leading cloth merchants decided to fund a daring expedition to find new markets beyond Europe. Their dream destination was China—or Cathay, as they knew it then. This was the world’s largest economy, accounting for more than a quarter of global GDP (England, by comparison, accounted for barely one per cent). The English merchants hoped that they would be able to exchange their cloth for silks, spices and other luxuries. The trouble was, they knew next to nothing about the lands to the East. They took as gospel the writings of Marco Polo, even though the Venetian had been dead for more than 250 years. To their credit, they realised their ignorance. So, as they prepared their ships for the great adventure, they turned to Eden, a gifted linguist, and commissioned him to gather every scrap of information he could about the lands the sailors might encounter on their route to China. Hurriedly, Eden translated great chunks of text from the writings of a German professor, Sebastian Münster, who himself had collected information from various sources (many of dubious reliability). The result was A Treatyse of the Newe India. Published in 1553, it was designed as a briefing paper for the sailors and as a kind of marketing brochure for investors. I first encountered Richard Eden while conducting research for my new book, New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (which is published by Little, Brown & Co and comes out on 20 March 2018). The voyage of 1553 was the first in an unbroken chain of expeditions that led—fifty years later—to the permanent settling of America by English-speaking peoples in the early 1600s. The sailors never made it to China. They only got as far as Russia. But this, in itself, was hailed as an achievement. Not since King Harold, who was defeated by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, had England enjoyed direct trading relations with the people of Muscovy. A new expedition was launched, and once again, Eden was asked to prepare an expanded volume. Published in 1555, the Decades of the Newe Worlde, featured translations of mainland European writers, notably Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, an Italian scholar who worked in the Spanish court in the early 1500s. It was hugely influential. In a memorable passage, he wrote of the “great China, whose king is thought…the greatest prince in the world”. This simple, unassuming sentence introduced the word “China” into the English language. However, for many years, the word “Cathay”, deriving from “Khitai” (the land of the Khitans, who held sway in northern China in the tenth century), remained the preferred English designation for the Middle Kingdom. In 1576, a group of merchants founded the Company of Cathay in order to fund voyages to China via the fabled Northwest Passage through the icy waterways of the Canadian Arctic (they never succeeded). This was also the year that Eden died, still in his mid-50s. There are no surviving portraits of the man—but what a legacy he left behind. And his contribution to the English language was not limited to the word “China”. “Brazil”, “cacoa” (the preferred spelling of the source of chocolate before it was supplanted by “cocoa”), “cannibal”, “canoe”, “pole star”, “Vatican”—these, among many other words, can be traced back to Eden’s work. Another word sums up Richard Eden’s contribution to the English language: the word “globe”, as in “the Earth”. Before 1555, it simply meant a sphere (from the Latin). Afterwards, it signified the world. At the end of the sixteenth century, when William Shakespeare was thinking about what to call his new theatre on the south bank of the Thames in London, he eventually settled on “The Globe”. It was not just that the theatre was spherical. He knew, as one of his characters in As You Like It once declaimed, that “all the world’s a stage”. So, through his work for English merchants, and the people they were sending on voyages of discovery, Eden provided Shakespeare—and ultimately all English-speaking peoples—with a new vocabulary to talk (and think) about the rest of the world. In doing so, he helped them lift their ambitions, and see far beyond the horizon. For more on New World, Inc: www.newworldincbook.com It is more than 20 years since the story broke that first got me interested in Cheddar Man—the hunter-gatherer now dubbed "the first Brit", whose skeletal remains, dating back around 10,000 years to the end of the last Ice Age, were found in 1903 in Cheddar Gorge in Somerset.

I had just started working for the Financial Times, and George Parker, now the newspaper’s political editor, called me to say: “Are you related to the man in the news?” In all the newspapers (although not, as I recall, the FT), there were photos of the man in the news. He was crouching beside some replica skeletal remains (the real ones are housed in the Natural History Museum in London) in a cave in Cheddar Gorge. I knew why George was asking me. The man in the news was called Adrian Targett, a 42-year-old history teacher. In a pioneering DNA project, led by Bryan Sykes, now emeritus professor of human genetics at Oxford University, scientists succeeded in extracting some DNA from one of Cheddar Man’s teeth (which were in good condition, and suggested a healthy diet) and compared it to the DNA drawn from the saliva of some of Cheddar’s residents. The researchers found that Mr Targett shared some of Cheddar Man’s DNA—they were, in a distant way, related. I told George: “I don’t think I’m related (at least, not to my knowledge)—but I do like my steaks rare” (which was a joke, but also true). As it turned out, the DNA extracted from Cheddar Man was mitochondrial DNA, which is passed through the female line. So Mr Targett’s link to the caveman was through his mother’s family—not his father’s. The surname was a red herring (although there is a high concentration of Targetts in the west country). Nevertheless, the story sparked my renewed interest in family history. As a kid, long before the first episode of the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? (which I think is terrific, by the way), I was taking out books on genealogy and “searching for your ancestors” from the local library. I had been fascinated by Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family—which I read after seeing the spectacular miniseries on television in the late 1970s. Sometimes, my enthusiasm was such that I fired off notes to elderly relatives, appealing for information. Bit by bit, I assembled a patchy family tree. Nowadays, with so many wonderful documents available online, the task of putting together a family tree is much easier. Getting back to the late 1700s—on one side of the family or the other—is not difficult. And very rewarding. But getting back 10,000 years? Wow. The latest extraordinary breakthrough—with scientists from the Natural History Museum and University College London analysing fresh samples of Cheddar Man’s DNA and showing that he had dark skin and blue eyes—brings those far-off times ever closer. Recently, I took a DNA test with Ancestry.com, which claims to track the DNA story of the past 2,000 years. It provided me with a fascinating window into my genetic past—and evidently a long and continuous presence in the British Isles. So perhaps, I can claim some kind of link with Cheddar Man. I can but dream… The other thing that the Cheddar story sparked was my fascination in origins. And I’ve pursued this in my latest project, New World, Inc—a history of the founding of America. The Pilgrims provide the founding myth of the United States—and the unifying celebration that is Thanksgiving. But, to really understand America today, it is necessary to go further back—to the English merchants and their associates who, for 70 years before the Pilgrims voyaged West, inched their way towards America. Largely forgotten now, they infused America with its defining spirit of entrepreneurship, self-determination and sense of destiny. For more on New World, Inc: www.newworldincbook.com For more on Cheddar Man/the first Brit: www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/cheddar-man-mesolithic-britain-blue-eyed-boy.html For the original Cheddar Man story: www.nytimes.com/1997/03/24/world/tracing-your-family-tree-to-cheddar-man-s-mum.html

It beautifully captures the cool confidence of a wealthy young man, who dons a delicate satin doublet and a dark, richly textured fur-lined gown. It is almost as if the picture is “taken”, like a photo, rather than “painted” with oils and brush strokes. Your eyes lock into his. For a moment, you are there with him, opposite him, in Tudor England.

At this time, German merchants—Born was from Cologne—enjoyed significant trading privileges in England. They controlled around one third of England’s cloth exports to mainland Europe—to the extent that the North Sea was known as Mare Germanicus, the German Sea. In return, they were expected to supply England’s navy with vital supplies from the Baltic: in particular, timber for ship building, as well as hemp, pitch and tar. Born would have been involved in this business. Indeed, he also supplied military equipment to Henry VIII’s armourer—weapons used in the suppression of rebellions in the north of England. For various reasons, Derich Born was expelled from London in 1541, and he was last heard of in 1549. By then, London’s merchants were starting to protest loudly about the fact that the Hanseatic merchants commanded such a large proportion of England’s cloth exports. Thomas Gresham, who later founded the Royal Exchange and Gresham College (and gave his name to Gresham's Law), led the protest. Eventually, in February 1552, after Gresham called for “the overthrow of the Steelyard”, Edward VI, Henry VIII’s son, withdrew the German merchants’ privileges. Although the Hanseatic merchants returned to favour under Queen “Bloody” Mary I, they never regained their grip on England’s cloth business. As I explain in my book New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (co-written with John Butman, and published by Little, Brown on 20 March 2018), the London merchants’ successful overturning of the long-held privileges of the merchants of the Hanseatic League was a significant milestone in the emergence of London as Europe's financial capital. At last, they could control a greater share of England’s exports of cloth—which was the country’s principal product—to mainland Europe. But they realised that this victory would not be sufficient to rescue England’s failing economy. The fact was that fewer people wanted to buy English cloth. In 1549, England exported more than 132,000 cloths—as lengths of fabric were called. By 1552, this had slumped to about 85,000. As one merchant observed, the economy was “waxing cold and in decay". To address this, they resolved to look for new markets for their cloth—beyond Europe. At first, they headed East towards Cathay, or China. They never got there. Eventually, they turned West, and stumbled upon North America. The rest, as they say, is history. For more: www.newworldincbook.com

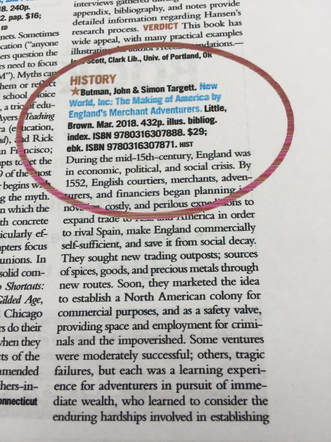

Here it is:

HISTORY *Butman, John & Simon Targett. New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers. Little, Brown. Mar. 2018. 432p. illus. bibliog. index. ISBN 9780316307888. $29; ebk. ISBN 9780316307871. HIST During the mid-16th-century, England was in economic, political, and social crisis. By 1552, English courtiers, merchants, adventurers, and financiers began planning innovative, costly, and perilous expeditions to expand trade to Asia and America in order to rival Spain, make England commercially self-sufficient, and save it from social decay. They sought new trading outposts; sources of spices, goods, and precious metals through new routes. Soon, they marketed the idea to establish a North American colony for commercial purposes, and as a safety valve, providing space and employment for criminals and the impoverished. Some ventures were moderately successful; others, tragic failures, but each was a learning experience for adventurers in pursuit of immediate wealth, who learned to consider the enduring hardships involved in establishing a new outpost or a sustainable colony. Butman (Breaking Out) and journalist Targett draw from a wealth of archival resources to argue convincingly that the commercial motive was key to English expansion into the New World. They successfully quash the 19th-century myth, manufactured by anti-slavery New Englanders, that virtuous, religious-freedom-seeking Puritans, not Southern slave-holding Virginians, were the real founders of the American Dream. VERDICT This engrossing history of adventure and innovation, disclosing the true motive for America’s founding, will appeal to all readers.—Margaret Kappanadze, Elmira Coll. Lib., NY

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed