organised these voyages. A serial entrepreneur, the driving impulse for his space activity is a looming apocalypse. In his public pronouncements on his project to send a manned mission to Mars, Musk points to the likelihood of a “doomsday event”. He doesn’t know when it will happen, but he is certain that it will happen, and human beings need to be ready to evacuate the world. Likewise, Musk’s predecessors took action when England experienced its own existential crisis in the 1550s, after a cataclysmic economic collapse threatened to weaken the country and leave it at the mercy of larger, richer neighbours such as Spain and France. Staring national oblivion in the face, they put their petty rivalries aside and put their capital to work in the first of an unbroken chain of voyages in search of new markets that led, ultimately, to the settling of America in the early 1600s. Musk’s answer to the apocalyptic challenge has been to create a company, SpaceX. Its corporate motto is “Making Life Multiplanetary”. Similarly, the English merchants answer was to create a private company—the wonderfully named “Mysterie, Company, and Fellowship of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions, Islands, and Places Unknown.” But, in setting up a company, they were doing something truly innovative. The “Mysterie” was arguably the world’s first joint-stock company and, as such, the forerunner of all modern corporations, including SpaceX. For the next 50 years, these merchants and their successors inched their way towards America. Often, progress was slow: one step forwards, two steps back. But in the early 1600s, a more advanced version of the “Mysterie” emerged in the shape of the Virginia Company. Tasked with establishing a colony in what was then called Virginia, it was led by a man named Sir Thomas Smythe, who faced many of the same challenges as Musk today. The first was—and is—to “get there”. This wasn’t, and isn’t, easy. Although Smythe no doubt benefited from the fact that Europeans had crisscrossed the Atlantic for more than a century, the journey across the north Atlantic remained perilously unpredictable and there was still no English colony in North America. Similarly, although Musk is building on a long history of aeronautical endeavour—rockets have reached the Moon and robots have been sent to Mars—there has never been a manned mission to the Red Planet. Musk has designed the Falcon Heavy rocket, which underwent a recent successful blast-off, and caused CNN to talk of “a new space age”. At the same time, he is developing the so-called BFR transport system featuring a spaceship for astronauts. Smythe’s equivalent was the Sea Venture—a 250-ton ship purpose-built to carry colonists, not just cargo, to Jamestown. But unforeseen accidents can happen. Although the Falcon Heavy was launched without a hitch, a previous rocket blew up in a pre-launch test, forcing Musk to modify the likely time of a mission launch. Likewise, the Sea Venture was hit by a hurricane and broke up on the rocky reefs of the Bermuda Islands—or the Devil’s Islands, as they were known then. The sense of loss was deeply felt across England—to the extent that William Shakespeare drew on the dark episode for his final play, The Tempest. As it happened, everyone on the Sea Venture survived the shipwreck. But there was no satellite tracking system in those days, and the news took more than a year to filter back to England. By then, Smythe and his associates had solved the problem of “getting there”—time and time again. But getting there is one thing, “staying there” quite another. Smythe was haunted by the memory of Roanoke, the first English colony, which had been established by Sir Walter Ralegh in what is now North Carolina. The first settlers abandoned the place. A second group were left behind to fend for themselves—and they were never seen again. Unlike Matt Damon, in the movie The Martians, there was to be no happy ending for these pioneers. They entered American legend as “the lost colonists”. Smythe resolved to send regular supplies of food, clothing and other necessities. But it did not become self-sustaining until some settlers found new ways to make money—notably, by farming tobacco and leasing land. Eventually, the call went out for skilled artisans to help build the colony—and there were plenty of people willing to sign up. Musk’s Mars colony may follow a similar trajectory. There is already speculation that settlers could fund a colony by mining minerals from the nearby asteroid belt or by producing a pipeline of scientific innovations that could be patented. And Musk has said that, eventually, a Martian settlement will see “an explosion of entrepreneurial activity because Mars will need everything from iron foundries to pizza joints and night clubs”. But it will take years and years to make Mars sustainable—as it did with America. It was competition that ultimately spurred Smythe and his fellow London merchants to success: they rushed to beat rival Plymouth merchants to America and, under the terms of a royal charter, have the pick of the places to settle in Virginia. And it will be competition that spurs Musk. He is in a race to be the first to Mars—and he is currently targeting 2024 for the first manned mission to Mars. That’s a decade ahead of NASA. But Musk is not just in a race against rivals. He is in a race against time. In fact, we all are. And it is here that the two projects—the mission to Mars and the voyage to America—start to diverge. If English merchants had not triggered their search for new markets that led, after half a century of endeavour, to the settling of America, then England may not have survived as an independent nation, America may not have become the country it is today, and English may not have become the world’s lingua franca. Such are the “ifs” of history. But if Musk and other likeminded entrepreneurs fail to find a way to colonise Mars, and ultimately other planets, then the future of the human race is at stake. As Stephen Hawking, the English astrophysicist who died last month, once said, we face annihilation from several possible calamities: “It could be an asteroid hitting the Earth. It could be a new virus, climate change, nuclear war, artificial intelligence gone rogue.” For this reason, he said, he was “convinced” that “humans need to leave Earth and make a new home on another planet.” And we need to do so quickly. “For humans to survive,” he warned, “I believe we must have the preparations in place within 100 years.” It is a mighty task that has befallen our generation. Musk is leading the way, along with a few other entrepreneurs. Others are sure to follow. Perhaps the real story of who made America—England’s merchants, not her Pilgrims—can provide all of us with the inspiration to succeed. For England, read the human race. For America, read Mars—and survival in a new world. To purchase New World, Inc: The Making of America by England's Merchant Adventurers (Little, Brown, 2018): www.amazon.com/New-World-Inc-Englands-Adventurers/dp/0316307882/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1525107581&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc

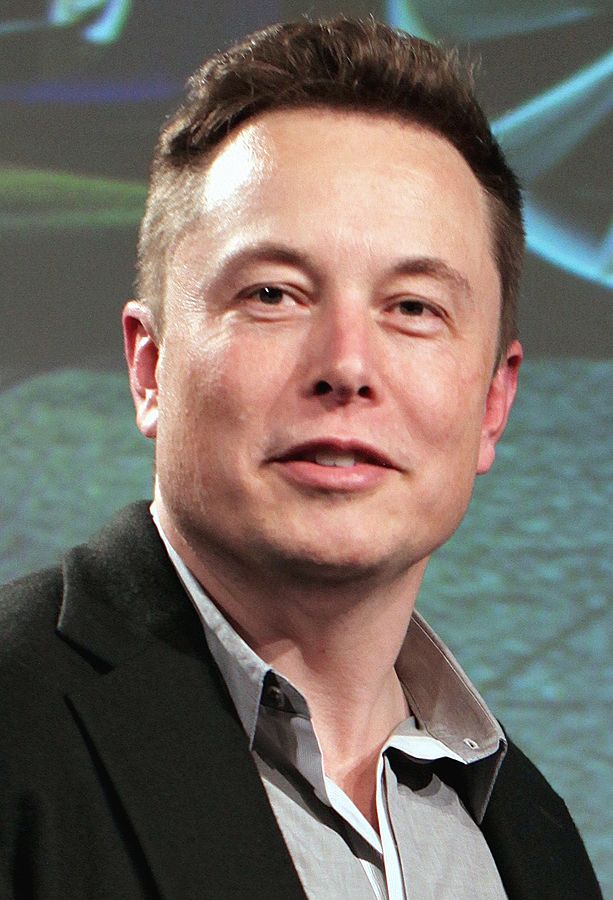

To pre-order (in the UK) New World, Inc: How England's Merchant Adventurers Founded America and Launched the British Empire (Atlantic Books, 5 July 2018): www.amazon.co.uk/New-World-Inc-Englands-Merchants/dp/1786495473/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1525107760&sr=1-1&keywords=new+world+inc For more on Elon Musk's Mars plans: www.spacex.com/mars Elon Musk photo: By Steve Jurvetson -https://www.flickr.com/photos/jurvetson/18659265152/CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40974345 Sir Thomas Smythe portrait: By Simon Van De Passe. National Portrait Gallery

1 Comment

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed