But, whatever its etymology, there is no doubt about the identity of the person who introduced the word “China” into the English language. His name was Richard Eden, a 35-year-old Cambridge scholar, who was working for a group of London merchants more than 450 years ago.

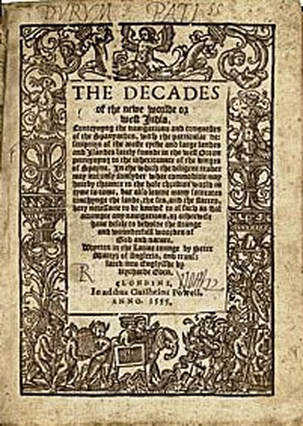

Born around 1520, when the tyrant Tudor monarch Henry VIII was on the throne (and still on his first marriage), Eden showed early promise as a student, advancing to Christ’s College, Cambridge when he was about 14 years old. He later moved to Queens’ College where, unusually for that time, he completed his bachelor’s degree. By the early 1550s, he was one of several brilliant young Cambridge men who occupied prominent positions at the court of the boy-king Edward VI, Henry’s son who had come to the throne at the tender age of nine—notably William Cecil, the administrator (whose descendants include the earls of Salisbury), Thomas Gresham, the merchant and financier (who gave his name to Gresham’s Law), and John Dee, the mathematician and cosmographer. This was a bleak time in England. Woollen cloth had long been the country’s principal source of income. As one contemporary noted: if one were to “divide our native commodities into ten parts…nine arise from the sheep’s back.” Yet, in the space of a couple of years, the market for English cloth in mainland Europe completely collapsed. Facing ruin, several of the leading cloth merchants decided to fund a daring expedition to find new markets beyond Europe. Their dream destination was China—or Cathay, as they knew it then. This was the world’s largest economy, accounting for more than a quarter of global GDP (England, by comparison, accounted for barely one per cent). The English merchants hoped that they would be able to exchange their cloth for silks, spices and other luxuries. The trouble was, they knew next to nothing about the lands to the East. They took as gospel the writings of Marco Polo, even though the Venetian had been dead for more than 250 years. To their credit, they realised their ignorance. So, as they prepared their ships for the great adventure, they turned to Eden, a gifted linguist, and commissioned him to gather every scrap of information he could about the lands the sailors might encounter on their route to China. Hurriedly, Eden translated great chunks of text from the writings of a German professor, Sebastian Münster, who himself had collected information from various sources (many of dubious reliability). The result was A Treatyse of the Newe India. Published in 1553, it was designed as a briefing paper for the sailors and as a kind of marketing brochure for investors. I first encountered Richard Eden while conducting research for my new book, New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (which is published by Little, Brown & Co and comes out on 20 March 2018). The voyage of 1553 was the first in an unbroken chain of expeditions that led—fifty years later—to the permanent settling of America by English-speaking peoples in the early 1600s. The sailors never made it to China. They only got as far as Russia. But this, in itself, was hailed as an achievement. Not since King Harold, who was defeated by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, had England enjoyed direct trading relations with the people of Muscovy. A new expedition was launched, and once again, Eden was asked to prepare an expanded volume. Published in 1555, the Decades of the Newe Worlde, featured translations of mainland European writers, notably Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, an Italian scholar who worked in the Spanish court in the early 1500s. It was hugely influential. In a memorable passage, he wrote of the “great China, whose king is thought…the greatest prince in the world”. This simple, unassuming sentence introduced the word “China” into the English language. However, for many years, the word “Cathay”, deriving from “Khitai” (the land of the Khitans, who held sway in northern China in the tenth century), remained the preferred English designation for the Middle Kingdom. In 1576, a group of merchants founded the Company of Cathay in order to fund voyages to China via the fabled Northwest Passage through the icy waterways of the Canadian Arctic (they never succeeded). This was also the year that Eden died, still in his mid-50s. There are no surviving portraits of the man—but what a legacy he left behind. And his contribution to the English language was not limited to the word “China”. “Brazil”, “cacoa” (the preferred spelling of the source of chocolate before it was supplanted by “cocoa”), “cannibal”, “canoe”, “pole star”, “Vatican”—these, among many other words, can be traced back to Eden’s work. Another word sums up Richard Eden’s contribution to the English language: the word “globe”, as in “the Earth”. Before 1555, it simply meant a sphere (from the Latin). Afterwards, it signified the world. At the end of the sixteenth century, when William Shakespeare was thinking about what to call his new theatre on the south bank of the Thames in London, he eventually settled on “The Globe”. It was not just that the theatre was spherical. He knew, as one of his characters in As You Like It once declaimed, that “all the world’s a stage”. So, through his work for English merchants, and the people they were sending on voyages of discovery, Eden provided Shakespeare—and ultimately all English-speaking peoples—with a new vocabulary to talk (and think) about the rest of the world. In doing so, he helped them lift their ambitions, and see far beyond the horizon. For more on New World, Inc: www.newworldincbook.com

1 Comment

3/4/2021 02:00:31 pm

Your blog is very useful and provides tremendous facts. Keep up the good work. Thanks for your publication.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed