But, whatever its etymology, there is no doubt about the identity of the person who introduced the word “China” into the English language. His name was Richard Eden, a 35-year-old Cambridge scholar, who was working for a group of London merchants more than 450 years ago.

Born around 1520, when the tyrant Tudor monarch Henry VIII was on the throne (and still on his first marriage), Eden showed early promise as a student, advancing to Christ’s College, Cambridge when he was about 14 years old. He later moved to Queens’ College where, unusually for that time, he completed his bachelor’s degree. By the early 1550s, he was one of several brilliant young Cambridge men who occupied prominent positions at the court of the boy-king Edward VI, Henry’s son who had come to the throne at the tender age of nine—notably William Cecil, the administrator (whose descendants include the earls of Salisbury), Thomas Gresham, the merchant and financier (who gave his name to Gresham’s Law), and John Dee, the mathematician and cosmographer. This was a bleak time in England. Woollen cloth had long been the country’s principal source of income. As one contemporary noted: if one were to “divide our native commodities into ten parts…nine arise from the sheep’s back.” Yet, in the space of a couple of years, the market for English cloth in mainland Europe completely collapsed. Facing ruin, several of the leading cloth merchants decided to fund a daring expedition to find new markets beyond Europe. Their dream destination was China—or Cathay, as they knew it then. This was the world’s largest economy, accounting for more than a quarter of global GDP (England, by comparison, accounted for barely one per cent). The English merchants hoped that they would be able to exchange their cloth for silks, spices and other luxuries. The trouble was, they knew next to nothing about the lands to the East. They took as gospel the writings of Marco Polo, even though the Venetian had been dead for more than 250 years. To their credit, they realised their ignorance. So, as they prepared their ships for the great adventure, they turned to Eden, a gifted linguist, and commissioned him to gather every scrap of information he could about the lands the sailors might encounter on their route to China. Hurriedly, Eden translated great chunks of text from the writings of a German professor, Sebastian Münster, who himself had collected information from various sources (many of dubious reliability). The result was A Treatyse of the Newe India. Published in 1553, it was designed as a briefing paper for the sailors and as a kind of marketing brochure for investors. I first encountered Richard Eden while conducting research for my new book, New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (which is published by Little, Brown & Co and comes out on 20 March 2018). The voyage of 1553 was the first in an unbroken chain of expeditions that led—fifty years later—to the permanent settling of America by English-speaking peoples in the early 1600s. The sailors never made it to China. They only got as far as Russia. But this, in itself, was hailed as an achievement. Not since King Harold, who was defeated by William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, had England enjoyed direct trading relations with the people of Muscovy. A new expedition was launched, and once again, Eden was asked to prepare an expanded volume. Published in 1555, the Decades of the Newe Worlde, featured translations of mainland European writers, notably Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, an Italian scholar who worked in the Spanish court in the early 1500s. It was hugely influential. In a memorable passage, he wrote of the “great China, whose king is thought…the greatest prince in the world”. This simple, unassuming sentence introduced the word “China” into the English language. However, for many years, the word “Cathay”, deriving from “Khitai” (the land of the Khitans, who held sway in northern China in the tenth century), remained the preferred English designation for the Middle Kingdom. In 1576, a group of merchants founded the Company of Cathay in order to fund voyages to China via the fabled Northwest Passage through the icy waterways of the Canadian Arctic (they never succeeded). This was also the year that Eden died, still in his mid-50s. There are no surviving portraits of the man—but what a legacy he left behind. And his contribution to the English language was not limited to the word “China”. “Brazil”, “cacoa” (the preferred spelling of the source of chocolate before it was supplanted by “cocoa”), “cannibal”, “canoe”, “pole star”, “Vatican”—these, among many other words, can be traced back to Eden’s work. Another word sums up Richard Eden’s contribution to the English language: the word “globe”, as in “the Earth”. Before 1555, it simply meant a sphere (from the Latin). Afterwards, it signified the world. At the end of the sixteenth century, when William Shakespeare was thinking about what to call his new theatre on the south bank of the Thames in London, he eventually settled on “The Globe”. It was not just that the theatre was spherical. He knew, as one of his characters in As You Like It once declaimed, that “all the world’s a stage”. So, through his work for English merchants, and the people they were sending on voyages of discovery, Eden provided Shakespeare—and ultimately all English-speaking peoples—with a new vocabulary to talk (and think) about the rest of the world. In doing so, he helped them lift their ambitions, and see far beyond the horizon. For more on New World, Inc: www.newworldincbook.com

1 Comment

It is more than 20 years since the story broke that first got me interested in Cheddar Man—the hunter-gatherer now dubbed "the first Brit", whose skeletal remains, dating back around 10,000 years to the end of the last Ice Age, were found in 1903 in Cheddar Gorge in Somerset.

I had just started working for the Financial Times, and George Parker, now the newspaper’s political editor, called me to say: “Are you related to the man in the news?” In all the newspapers (although not, as I recall, the FT), there were photos of the man in the news. He was crouching beside some replica skeletal remains (the real ones are housed in the Natural History Museum in London) in a cave in Cheddar Gorge. I knew why George was asking me. The man in the news was called Adrian Targett, a 42-year-old history teacher. In a pioneering DNA project, led by Bryan Sykes, now emeritus professor of human genetics at Oxford University, scientists succeeded in extracting some DNA from one of Cheddar Man’s teeth (which were in good condition, and suggested a healthy diet) and compared it to the DNA drawn from the saliva of some of Cheddar’s residents. The researchers found that Mr Targett shared some of Cheddar Man’s DNA—they were, in a distant way, related. I told George: “I don’t think I’m related (at least, not to my knowledge)—but I do like my steaks rare” (which was a joke, but also true). As it turned out, the DNA extracted from Cheddar Man was mitochondrial DNA, which is passed through the female line. So Mr Targett’s link to the caveman was through his mother’s family—not his father’s. The surname was a red herring (although there is a high concentration of Targetts in the west country). Nevertheless, the story sparked my renewed interest in family history. As a kid, long before the first episode of the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? (which I think is terrific, by the way), I was taking out books on genealogy and “searching for your ancestors” from the local library. I had been fascinated by Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family—which I read after seeing the spectacular miniseries on television in the late 1970s. Sometimes, my enthusiasm was such that I fired off notes to elderly relatives, appealing for information. Bit by bit, I assembled a patchy family tree. Nowadays, with so many wonderful documents available online, the task of putting together a family tree is much easier. Getting back to the late 1700s—on one side of the family or the other—is not difficult. And very rewarding. But getting back 10,000 years? Wow. The latest extraordinary breakthrough—with scientists from the Natural History Museum and University College London analysing fresh samples of Cheddar Man’s DNA and showing that he had dark skin and blue eyes—brings those far-off times ever closer. Recently, I took a DNA test with Ancestry.com, which claims to track the DNA story of the past 2,000 years. It provided me with a fascinating window into my genetic past—and evidently a long and continuous presence in the British Isles. So perhaps, I can claim some kind of link with Cheddar Man. I can but dream… The other thing that the Cheddar story sparked was my fascination in origins. And I’ve pursued this in my latest project, New World, Inc—a history of the founding of America. The Pilgrims provide the founding myth of the United States—and the unifying celebration that is Thanksgiving. But, to really understand America today, it is necessary to go further back—to the English merchants and their associates who, for 70 years before the Pilgrims voyaged West, inched their way towards America. Largely forgotten now, they infused America with its defining spirit of entrepreneurship, self-determination and sense of destiny. For more on New World, Inc: www.newworldincbook.com For more on Cheddar Man/the first Brit: www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/cheddar-man-mesolithic-britain-blue-eyed-boy.html For the original Cheddar Man story: www.nytimes.com/1997/03/24/world/tracing-your-family-tree-to-cheddar-man-s-mum.html

It beautifully captures the cool confidence of a wealthy young man, who dons a delicate satin doublet and a dark, richly textured fur-lined gown. It is almost as if the picture is “taken”, like a photo, rather than “painted” with oils and brush strokes. Your eyes lock into his. For a moment, you are there with him, opposite him, in Tudor England.

At this time, German merchants—Born was from Cologne—enjoyed significant trading privileges in England. They controlled around one third of England’s cloth exports to mainland Europe—to the extent that the North Sea was known as Mare Germanicus, the German Sea. In return, they were expected to supply England’s navy with vital supplies from the Baltic: in particular, timber for ship building, as well as hemp, pitch and tar. Born would have been involved in this business. Indeed, he also supplied military equipment to Henry VIII’s armourer—weapons used in the suppression of rebellions in the north of England. For various reasons, Derich Born was expelled from London in 1541, and he was last heard of in 1549. By then, London’s merchants were starting to protest loudly about the fact that the Hanseatic merchants commanded such a large proportion of England’s cloth exports. Thomas Gresham, who later founded the Royal Exchange and Gresham College (and gave his name to Gresham's Law), led the protest. Eventually, in February 1552, after Gresham called for “the overthrow of the Steelyard”, Edward VI, Henry VIII’s son, withdrew the German merchants’ privileges. Although the Hanseatic merchants returned to favour under Queen “Bloody” Mary I, they never regained their grip on England’s cloth business. As I explain in my book New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers (co-written with John Butman, and published by Little, Brown on 20 March 2018), the London merchants’ successful overturning of the long-held privileges of the merchants of the Hanseatic League was a significant milestone in the emergence of London as Europe's financial capital. At last, they could control a greater share of England’s exports of cloth—which was the country’s principal product—to mainland Europe. But they realised that this victory would not be sufficient to rescue England’s failing economy. The fact was that fewer people wanted to buy English cloth. In 1549, England exported more than 132,000 cloths—as lengths of fabric were called. By 1552, this had slumped to about 85,000. As one merchant observed, the economy was “waxing cold and in decay". To address this, they resolved to look for new markets for their cloth—beyond Europe. At first, they headed East towards Cathay, or China. They never got there. Eventually, they turned West, and stumbled upon North America. The rest, as they say, is history. For more: www.newworldincbook.com

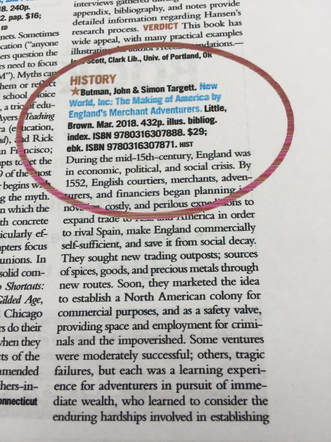

Here it is:

HISTORY *Butman, John & Simon Targett. New World, Inc: The Making of America by England’s Merchant Adventurers. Little, Brown. Mar. 2018. 432p. illus. bibliog. index. ISBN 9780316307888. $29; ebk. ISBN 9780316307871. HIST During the mid-16th-century, England was in economic, political, and social crisis. By 1552, English courtiers, merchants, adventurers, and financiers began planning innovative, costly, and perilous expeditions to expand trade to Asia and America in order to rival Spain, make England commercially self-sufficient, and save it from social decay. They sought new trading outposts; sources of spices, goods, and precious metals through new routes. Soon, they marketed the idea to establish a North American colony for commercial purposes, and as a safety valve, providing space and employment for criminals and the impoverished. Some ventures were moderately successful; others, tragic failures, but each was a learning experience for adventurers in pursuit of immediate wealth, who learned to consider the enduring hardships involved in establishing a new outpost or a sustainable colony. Butman (Breaking Out) and journalist Targett draw from a wealth of archival resources to argue convincingly that the commercial motive was key to English expansion into the New World. They successfully quash the 19th-century myth, manufactured by anti-slavery New Englanders, that virtuous, religious-freedom-seeking Puritans, not Southern slave-holding Virginians, were the real founders of the American Dream. VERDICT This engrossing history of adventure and innovation, disclosing the true motive for America’s founding, will appeal to all readers.—Margaret Kappanadze, Elmira Coll. Lib., NY

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed